It is a testament to the scope and depth of Platon’s design that, in many ways, the easiest part of his plan was the forging of gods out of the primordial shards he had secured for each City. The people of the Old Dominion, after all, had been shaped by a theocracy, their everyday life dominated by a religious culture, forged by a mosaic of multiple tribes and peoples, as well as an expansive pantheon. Stripped from its idealistic endgame of a perfect society, Platon’s enterprise was a true scientific miracle that saw gods created by the design of a mortal, an unparalleled success of human ingenuity.

The shackles that contained these new gods, each further restricted in the confines of worship and influence of their respective City States, were indeed placed ingeniously. But the strength and endurance of their manacles relied on the creation of an ideal society where great philosopher kings ruled in harmony and wisdom. With that part of the plan in shambles, the chains of these deities would weaken, and cracks would prevail upon their gilded prisons; their limitations would suffer and the thirst for absolute freedom would slowly consume them. In most cases, this would fuel an unending power struggle between them and the City’s Scholae, academics and demagogues. But in some Cities the patron deities would expand their influence and purpose far beyond those of their intended roles.

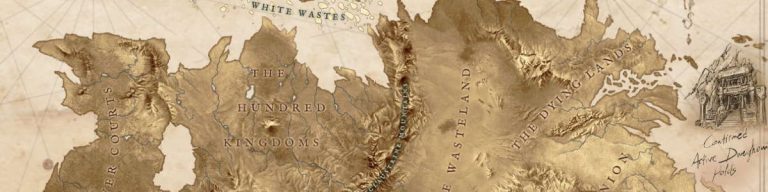

In Milios – by far the strongest naval power of the City States and a dominant force even beyond the pelaga of the Cities – while the goddess Athrastia does not dominate the everyday life and politics of her city, many see her influence behind the city’s admirals, who worship her as a fickle and vengeful mistress that mirrors their seas. But it is perhaps no coincidence that those deities that have far expanded on their intended roles were originally designed as a triumvirate of military command, there to ensure the safety of the City States. Whether because of the abundance of worshippers that their military societies offered, their very nature or chance, three gods above all else would come to dominate their Cities’ life and cultures.

In Tauria, Minos would be venerated with gusto, his double-edged axe adorning the shields of his warriors and his horns dominating his colorful city’s landscape. Celebrated by his people for his disposition, ever willing to break his own rules, but also feared for his stern judgment and even vengeful wrath, Minos is perhaps viewed as a Warrior King, one who makes allowances readily but whose mood-swings can be unpredictable once an unseen line is crossed. His critics often dismiss him as reckless, petty, and self-indulgent but an observant scholar would perhaps hesitate before adopting such views. Minos’ warriors are some of the best in the City States. For all the feasts and colorful celebrations, Tauria remains a heavily militarized and structured society. His warriors have defended their patron’s influence and lands from other City States, often through displays of power that one could portrait as unnecessary, petty or vengeful. Yet, the Warrior Bull has rarely turned his aggressive attention towards the City States unless provoked, some claim unwilling to risk disrupting the balances that still ensure the partial success of Platon’s plan. Tauria’s forces have instead ever looked to expand towards the Allerian Plains. Multiple campaigns and wars against the Telian Empire, or the Hundred Kingdoms later, have been waged, that, through both victory and defeat, have inspired timeless epics of legendary warriors, massive battles and heroic deaths.

Minos’ stricter and more ruthless counterpart reigns in Lycaon, where Aecos would ensure the city’s name would become a synonym for strength, cunning and ruthlessness. His efforts to break free of his shackles are as relentless and single-minded as they are calculative and patient. It is perhaps a blessing that Aecos’s limitations remain seemingly stronger than Minos’s but the deity is nothing if not a cunning commander. It is no coincidence that no city and few towns or settlements exist near his, and the entire Lycopaethion, the Valley of the Wolf, is riddled with ghost towns and abandoned ruins of temples to other deities. If directly challenged through force, the challenge is answered with spear and sword, quickly and efficiently, and it is said that even the Nords have learned tales of ruthless warriors with Lycaon’s initial on their shields. Still, Aecos understands that it is preferable to convert than to kill would-be followers and that the way to freedom is not a battle but a campaign. Where circumstances allowed, rather than eradicating a settlement, crops have been destroyed, land salted and animals stolen or killed, the missions often used as training for child cadets. In time, the would-be settlers would either leave or try their luck in the existing towns or the city. If they did not come to worship him, then their children or their children’s children would. Ever few of words and despising fanfare, Aecos would see Lycaon become a symbol of military strength that the entire world would come to know.

Last of the intended triumvirate was Radamanthos, patron of Acheron. Unlike his counterparts, Radamanthos was intended as a thinker and a strategist, not a mighty warrior or commander. Baptized as he was with one of the many names that once belonged to the Seer, the deity was soon venerated as a judge of the dead, and the god readily adopted the mantle, with eyes sternly turned to the rising threat in the East. It is perhaps for this reason that he approached both Minos and Lycaon, trying to ensure that all three fulfilled their intended roles as a triumvirate. And it is perhaps for the same reason that the two rejected his offer.

Afraid of the possibility of his own corruption without his counterparts and terribly aware of his duty as the first defense against Hazlia’s influence, Radamanthos turned to his worshippers. Choosing two, he attempted to replicate Platon’s experiment and to elevate two mortals by his side; Triptolemos in the place of Minos and Demophon in the place of Aecos. It is unknown precisely to what extent his endeavor was successful, or how effective his effort to counter his corruption has been. Under the three deities, however, Acheron has successfully endured and even prospered in the shadow and under the constant threat of the Old Dominion and the Tribes of the W’adrhûn. And yet whispers and shadows in the city seem alive of late. At the feet of Radamanthos’s giant statue that stares ever to the east, where Triptolemos and Demophon reside, a new inscription has appeared: “Θνητός γεγονώς άνθρωπε, μη φρόνει μέγα”: you were born mortal, Human, do not think too highly of yourself. While some see this as a wise caution from their gods, to remain humble and respectful, reminding them of the dangers of hubris, others fear both its origin and its true meaning.

With a careful selection by Platon, of names, iconography and symbolism, all familiar from the endless, vague and intricate scriptures of the Dominion, the transference of belief came to his designed deities almost naturally. Acheron’s seasons today are riddled with Mysteries, sacred days, rituals and celebrations to strengthen the triumvirate. Lesser or greater aspects that Hazlia had assimilated from his own Pantheon were once more redirected into these shards, depriving the Pantokrator of small but vital portions of the power and dominion he was possessing at the peak of his power. Shackled by the contingencies built in the process and method of their very creation, these new gods would wound Hazlia’s all-powerful eminence, while avoiding the dangers of corruption. But with those shackles gone, one can’t but wonder where the unintended expansion of these deities will lead.