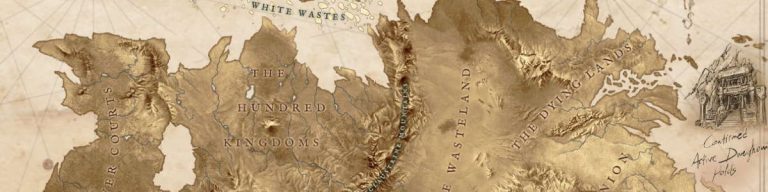

The prevailing theory among most from the rest of the Hundred Kingdoms is that “Riis” derives from “Russ” and that Riismark was originally settled by a Russ kin group. That is why, many claim, they call themselves Markmen instead, trying to distance themselves from the Principalities. This claim, however, the Markmen dismiss readily, claiming that Riis is in fact an old word for “rivers.” Riismark is the land of the Riverking, the legendary first King of the land who founded all eleven Kingdoms, and there is no love lost between the Russ and themselves. Historically, they are both wrong. The Markmen are in fact a Hermannic kin group and Riis is actually a degenerative word form of Reis, the Hermannic word for “rice,” one of Riismark’s earliest produces.

If ever there was a historical person behind the persona of the Riverking, he has long been forgotten, buried under layer upon layer of legendry. The more mundane reality is that the Riverking was but another King Without Court, or possibly there were several of them, trying to escape the influence and control of the Orders in the Heartlands. The prevailing theory is that Riismark was settled late or at least later than the battle of Yenik in 134 P.R. and it was a desperate choice that the settlers were forced into since the way east was blocked by the Russ. Historians base this assumption on the fact that the land must have looked very unappealing for settlement, filled with uninviting swamps and muddy ground, usually too wet and soft for the limited techniques of agriculture practiced at the time. It is perhaps for this reason that one of the fabled deeds of the Riverking was tricking the Brown Wyrm, Branschlange — the Riverking’s main antagonist — into giving him rice. Notoriously tolerant to being grown in submerged fields, rice has always been produced and consumed in Riismark and proved paramount to the early successful settlement of the land. In fact, some historians claim, the very term “Riverking” is a wrongly translated term for Reisköng or “Rice King” — possibly a nickname for one or many of Riismark’s early sovereigns.

While rice ensured the survival of those early settlers and even allowed the kings of the land to engage in modest trade with outsiders, Riismark would develop later in history, once much agricultural knowledge that had been lost after the Fall was remembered or reinvented. Finally, the rich soil of Riismark could be exploited by other things than almost exclusively rice. This allowed for proper castle-kingdoms to develop, following an evolution parallel — if a little slower — to those of the Heartlands. True to their legends of the Riverking and his Eleven Heirs, eleven castle-kings have dominated the political landscape of the province, vying for land and influence over the fields and rivers.

The true strength and source of riches of Riismark would come later, with the discovery of rich iron veins lying under the mud and even of modest veins of gold. All of a sudden, the entire province changed. While the rivers had always been deemed important and most castle-kings had raised their castles in strategic positions in order to oversee them, the increased need of trade routes saw extensive works being done. Since traditional roads proved impractical to pave and difficult to maintain, many rivers were widened at places, to ensure that large barges carrying raw materials could safely navigate them. To ensure control over the water-ways, most kingdoms forged gigantic chains from local steel to forcefully monitor and tax all movement in their rivers. Such chains are not only raised near the ports of the kingdoms’ castles but have in fact been placed on nearly every river junction to ensure that the quantities of goods are monitored multiple times, thus limiting smuggling. This has made Riismark Steel famously expensive; but its quality more than makes up for the elevated price.

This explosion changed how the entire world viewed Riismark; from an ignored island in a sea of Kingdoms surrounding it, Riismark was coveted by Russ and Kingdoms alike, almost overnight. If either expected the long-feuding castle-kings to be swayed or conquered easily, however, they were sorely disappointed. Long left to their own devices, the Markmen had developed their own culture and identity and, in the face of outsiders, their Kings were ready to defend it — along with their mines. The Alliance of the Eleven Steel Thrones, fueled by the myth of the Riverking and his Eleven Heirs, became the stuff of new legends, for Markmen and foreigners alike. Despite their efforts, however, they were sure to eventually fall, as the Russ Princes proved ready to throw all they had in order to lay claim over the land and its metals. The only thing that stopped them was the Eleven bending the knee to Charles II. They did so under one condition; Riismark would become a single province, with well-defined borders. In return, the Emperor’s Legions would buy Riismark Iron and Steel at significantly lower prices.

While the eleven castle-kings have never well and truly been at peace, with always some of them at least battling over land or control of the rivers, Riismark sovereigns retained a strong cooperation before outside threats, and its people have forged a strong sense of common identity — they are, in fact, one of the most recognized cultural groups of the modern Kingdoms. Markmen consider themselves divided into two peoples: the Riismen, those generally living in the castle-towns and chain stations on the rivers, and the Markeni, those generally living near the fields or the mine towns. But even for them, such distinctions hold little significance in the grand scheme of things.