Under a gold and crimson rain… Wasn’t that how the rhyme went?

He shook his head, and a regretful groan escaped his lips, before his hands rushed to cover his eyes and rub his temples. He felt dizzy, almost nauseous, and the light felt like it was piercing behind the eyes and through his skull, adding to the pounding headache that rushed to meet him in consciousness. Salt and bile struggled for reign over his mouth, and he could hear the soft roar of the sea—wait. No.

Leaves.

Leaves in the wind, dry autumn leaves, dancing with soft gales. He opened his eyes, hurriedly and wide, wincing from the light and dizziness. He was in the forest. Not too far from the sea—he could hear it now, distant, behind the dry rustling of autumn leaves—but far enough to not have come here without memory.

He sat up, eyes wide and alert, but mind struggling. He felt disoriented and lightheaded, unable to get his bearings, and scattered, faded memories, seemingly of a life-time ago but which couldn’t have been older than a day, flashed. Waves. Seagulls. Being lifted, dragged. Voices. The rustling of leaves. Words. Mhor. He remembered that word. Or did he?

…Under a gold and crimson rain…

“Eat.”

A voice was heard, sending cold shivers down his spine and he jumped up, startled, only to falter as vertigo came like a lead blanket to shove him down. He saw a wooden bowl, filled with nuts and pedals dancing on a milky broth.

“Eat,” he heard again. “Then wait.”

He heard someone move away in the forest, the dizziness withdrawing almost instantly. Only then did he realize how hungry he was, but he waited, then waited some more, his stomach growling. The command was not repeated, and nothing seemed to stir in the woods. He hesitated, fearful, and his mind raced. The files said they used their bonding power to learn one’s language but many feared that it meant they could read minds as well or, possibly, feel intentions. He should-

No. He scolded himself and forced the rhyme to his thoughts once more and this time he silently recited the whole rhyme:

A cunning mind, a heart of gold, matching the color of the leaves

A truth he speaks, a lie he acts, walking the path of fools and thieves

Now see the fool: under a gold and crimson rain, dances he.

The spy! The Thief! Under the trees he walks, but came he from the sea.

It worked, the trick they had devised to help him focus on the moment. True enough, soon there was no mission. No infiltration. No theatre. He was the Fisherman and no more.

Fear. Caution. Hunger. He eyed the bowl with hungry eyes. Did he dare eat?

Vote in the Living World!

Prelude

302 P.R.

“Colglough, come on,” Aisling said. “This is far enough.” She was giggling, but there was some nervousness in her voice. The young man’s green eyes flashed with mischief as he looked at her and stopped. This, she thought; this ever calmed her. Even in their most mischievous, his eyes promised. No harm, they whispered. His broad shoulders, expanding like the Cairn above as he turned to sit, agreed with the promise.

“Remember the song, did ya?” laughed the fire-haired man, as he pulled her down to sit with him, embracing her. She laughed herself, as she let herself be pulled on his lap, leaning her head back to rest next to his. Below, the land spread wide with a hint of morning mist remaining, the cattle of the clans like puffs of clouds against a green sky.

“Beware, beware..!” he mocked, singing in her ears.

“Hush!” she said, slapping gently his shoulder. “There is bravery and tomfoolery, Colglough U’Darr, and then there is plain foolishness. To provoke the Fae is the latter.”

“Let us appease them, then, wife,” the young man said. “The way the midwives say the ol’ones did…”

She laughed and called him a brute but did not resist. Later on, they were sitting, her head leaning back, her cheek against his once more, humming.

“Who is provoking them now, woman?” Colglough asked.

“I think they know we’re here already,” she said mischievously, and he laughed. “Should we get back?” she asked.

“’Tis early still,” he said. “And Pa said he won’t need me ‘till the Mallees come for the flock tithe, no sooner than midday.”

“The Mallees all but run the shire, husband. It would be wise to be on your best behavior.”

“The Mallees are bastards and will get what’s coming to them, you’ll see. We have an Emperor now, haven’t you heard? Even the Cadeyrn’s lackies will behave. Besides, I feel dizzy.”

“Aye, dizzy is a word,” she said. “Sleepy is another.” She smiled satisfied and closed her eyes relaxed, resuming her humming, sleep sneaking up on her, as she heard him sing:

Beware! Beware! Beyond go ne’er the green and brown gate!

For once inside, you cannot hide, the Forest Things await…

“Oh, you fool,” she muttered, stretching sleepily. “’Tis not a joke. The druidess, Niamh, says that-“

“I didn’t sing.” His voice was shaking, and it came from far, much further than it should be. It did not seem, in her dream, that he was taking to her.

I didn’t sing!

Eyes wide in terror, she got up and was alone. And that was the last Aisling U’Darr ever heard her husband’s voice.

348 PR.

“Two hunters of the Legion of Ash arrive to aid us! My, oh my, aren’t we the lucky ones, ey?”

Rain fell light, like spray from sea’s waves only sweeter and chilled, as they stood side by side before the Burgomaster. Nay, Allistor thought. Mayor she’s called here, he realized, surprised by how much their years away from home had changed their very thinking.

“It’s been years since little ol’ Farshire has received such attention,” the Mayor, Jonet Mallee, went on with a hefty laugh, a few stray droplets careening toward her under the hide awning that crowned the lodge’s entrance. “And for cattle!”

Allissaid dipped her chin at her brother and continued without pause, facing the stout Jonet. “Your bounty spoke of ill omens, esteemed burgomaster,” she said and Allistor smiled. They shared so many things and their mistakes among them. “The Ash would see them answered.”

“Aye,” confirmed Allistor without missing a beat. “You spoke of bloody murder, not cattle-snatching. Is it not so?”

“It is, lad, it is,” the stout woman said, nodding anxiously. “We had another one only this daybreak reported. By the Karnagh fields, up the hill, ye all know the place. We’ve woken up to sheep and cattle alike strewn across entire fields too many a time as of late. The guts and gore have pointed to one place each and every time,” the woman paused and turned, raising a single finger to point toward the woods that peeked over the easternmost hill. “I say its wolves that drag them to their lair. Them northern ones, the bloody barbarians bring, can be vicious and mean. But the people—you two know how they can be—insisted, and Kanasare of the druids agreed so…”

“You did well,” Allissaid answered. “The Ash would have the truth of it. This close to the mountains…”

“Oh! Suppose you are right!” interrupted Jonet. “And none of the local dare go there—beware the gates and all—in fear of… Well, you two should know best of what the Fae are capable of.”

The twins shared a knowing look, and, their voices now one, they spoke. “Well, we best get movin’ then!”

As they reached the forest’s edge, the rain began to dissipate, and silence—muddled only by the keening wind—settled in its stead. The aroma of wet soil and evergreen foliage permeated the air—yet it was not alone. Rot also caressed the nostrils of brother and sister alike, their senses honed by years of hunting down the abominable and the monstrous in service of the Ash Legion. Silent as a whisper, the duo moved closer to the woodland border, coming upon a sight all too expected. A non-local would have a hard time discerning what was now splayed before them: bits and pieces of flesh and sinew were peppered across the central site of the massacre. But…

“Hard to find a body whole or part, it is,” the Jonet suddenly said. “Every time. Such terrible the carnage.”

“Yes, quite the sight,” grumbled Allistor, raising his collar to cover his nose and mouth. “Indeed,” agreed Allissaid between a gag and a cough. They wouldn’t have been able to guess that they were cows, only a few patches of their woolly exteriors visible. “A bit too…”

“When you two enlisted, I honestly thought that was the last I’d see of you both!” the mayor said, leaning against the stone hedge marking the field. “What, especially after your granny, good ol’ Aisling, passed…” her gaze drooped and darkened at the mention, and so did those of the twins but they said naught to it.

“Good lady Mallee,” said Allissaid, “perhaps you best call for the shepherd. We’d hear his tale, if there is one to tell.”

“Oh, I can tell you all!” the mayor said, waving dismissively.

“The Legion would need us hear it from his mouth. Old Petten was it?”

“Petten the Young now,” the mayor said, “old Petten left us some time ago.” The twins nodded their sympathies but kept looking at her expectant so, after a while, she added quite disgruntled “I’ll better fetch him, then.”

“Our thanks, good Mayor,” Allissaid said, and they watched her take the winding path to the houses below the hill.

“Fancy seeing ye here!” he said turning to her with a mischievous smile, once the mayor was out of earshot.

“I just knew ye wouldn’t resist, ye stubborn oaf,” his twin chuckled, her clear sound such a stark contrast to the bloody mess around them. “Ye always took gran’s oath too serious. Where were ye posted?”

“Close,” he said. “A couple of days north of Burneaux. Had just finished bringing in a hedge witch. Took a leave when I saw the notice. Ye?”

“Closer still,” she answered. No hug, no greeting, part for fear of being watched, part because between them it was never needed. They both kept looking around the mayhem, their Legion training at good use as they scoured the site. “Galania, middle of nowhere but a week from Lantony. Drake tracking training. Heard a rumor, asked for leave and here I am. Quick thinking about telling her we came together.”

“She said it herself,” he smirked. “I just never corrected her.” She chuckled, shaking her head, and kept looking.

“I was about to say,” he went on. “A bit too extravagant, don’t you think?” The brother moved forward, pacing between the patches of gore and nudging a hacked-off limb with his boot—a blood-soaked curio lay underneath it, made of twigs and coarse hair, with more readily visible across the blood-soaked site. “Extrapolate, if it pleases you, sister.”

“Such violence, such waste—this is unlike the Fae,” mused Allissaid aloud, moving to her brother’s side.

“Call me superstitious,” responded the brother, “but I’d think greater powers would see us drawn to this place from such a distance—far apart and urging us to relinquish our official duties to boot…” The man paused. “Not to mention, such would not be above creatures that would readily snatch men and women away from their families. Grandma always said that the woods were inhabited by evil th—”

“Grandma Aisling, long may she be remembered, was bound to the past!” Allissaid lashed out with her tongue. “We must not let myths and grim tales cloud our judgment; this could be a ruse, a demented jest.” The woman moved without giving her brother the space to interject. “Jonet spoke of four killed cows, no? Well, I only see enough limbs to account for two. See, the hooves, they—”

“The rest could have been dragged into the woods proper. Besides, there’s this…” he lifted the charm with a stick; an old pattern, meant to protect against the Fae; a superstition, they both knew.”

“Since when did the Fae leave behind evidence of their ill-doings so openly? ‘Tis too convenient—”

“Maybe they’ve grown bolder—hungrier. Do not project your logic onto the eldritch; such weavers of demise follow no set rules…”

The pair ceased their arguing and turned, in perfectly timed unison, to gaze further into the forest. It was silent, that it was, and the passing howling of the wind and the rustling of leaves offered brief respite. “So be it, brother,” Allissaid was the first to speak. “You know of my opinion. I shan’t argue with you anymore… What would you have us do?”

Allistor looked around the field one last time, his words deciding the actions that will follow:

Choice

- “If we are dealing with the Fae, we must set up a trap. We must coax them out of the forest and into the open…”

- “You are right. My emotions got the best of me. This is clearly the work of a twisted yet human mind. We must follow the evidence into the forest and snuff them out!”

- “I can’t tell, dear sister—and, I gather, neither can you. We must head back into town and gather more information before we act.”

348 PR.

Allistor sighed and got up from kneeling close to the carnage.

“I say we hear what Petten has to say, before we draw conclusions,” he said in the end, though his eyes still wondered west. “Perhaps, perhaps I say, there something else afoot here. Perchance a feud’s at work that we don’t know about, ey?” he admitted.

“Perhaps. But why the trinket then?” Allisaid asked and motioned towards the charm, still dangling from the stick, then added with mischief in her eyes “and why aren’t ye holding it proper?”

“Pah!” he exclaimed and tossed them aside, stick and charm as one.

“See?” she pressured. “I told ye, ye take the oath too seriously. “Mamó was a gem but…”

“Mhór was who she was and we both know what that was,” he cut her off. “That doesn’t make her wrong or our oath any less of a burden. If not, ye wouldn’t be here.”

“I ain’t here for no oath, brother,” she said honestly. “I came because I knew ye’d come.”

“Ye’re a pain in my arse, sister,” he said, then looked at her, smiled and added. “It is good to see ye, Alli.” She nodded, motioning from her heart to him with a warm smile, then flashed him that grin she always flashed when she had won. He grunted and laughed and they left. The rain would stay away until the eve, they could tell, and soon the mist would roll in, so people, the Mayor and Petten included, would gather at the public house. They followed the path, chatting about their missions since last, they’d been posted together, over a year ago. True enough, like a grey, moist blanket unfolding, the mist haunted their steps, hiding the gruesome the carnage of the scene they’d left behind.

* * *

“A feud? Bless me, who’d feud with me for real, Al?”

The whole alehouse was filled with muffled chuckles. They’d welcomed them with smiles and caution in equal measure, not forgetting who they were, not forgetting that they’d left; even if it were to join the Ash. Now, they had been given space to talk to Petten, meaning people would pretend, at least, not to listen. They were failing, and the twins felt right at home.

“Come now, Pets,” Allisaid patted his hand. “Such a catch and nae loop to mark ye called for. Perhaps some scorned lass?”

“Which lass would stand for such blood and gore, ey?” Petten asked but regretted it before the words were out of his mouth. Not even trying to pretend, the Mayor and Leianne the barmaid, turned to look him and there followed a litanies of curses the likes of which would make a sailor blush. Alli was starring too and her, in truth, Petten believed; a warrior’s eyes, he noticed, weathered and burdened with sights best left unseen, behind that joyful glitter, like morning dew on an oak’s leaves catching the sun.

He gulped, for many reasons, and said. “All I meant was…” he whispered to her, as the litany was dying down, but Alli stopped him.

“I know what ye meant, Pets.”

“No,” the shepherd said, moving on. “No feuds, nor lasses scorned,” he said, and buried his face in the ale. “Besides, there were others. Ye think I’m in a guild as well, eh?” he tried to joke and chuckled. The twins smiled and he went on.

“I’d say it’d be them Things, ye know, of the Woods. But that seems an ugly thing to say to ye, me complaining about sheep while yer family…” Silence and blank stares were his answers so he drank some more and went on. “I found them at dawn. Before that was Shimmy; Shimmeagh U’Candar, ol’ Cokes’ boy. Four heads he says he lost, though only three they found, skulls impaled as if to mark the forest. Then, of course, a month ago, the mayor’s herd was hit, but that ye’d know. It’s why ye came, eh?” They nodded but stayed quite. No better way, they knew, to keep him talking than letting him talk. “Same thing, but only a head this time, the rest were scattered. This on’ was first and close to the woods, it was, that why we all urged the mayor to call for…”

“Wait, the U’Candar’s herd was not close to the forest?” Alli asked.

“Nay,” Petten shook his head. “His route goes east, close to the Way.”

“A long way for the Fae”—Petten, and others in the room, made the sign at the word—“to come,” Alli remarked, looking at Al. He simply nodded but said nothing and Petten jumped in.

“Aye, it were,” he said. “Ye ask me, I thought they gotten mad, see, for the Mayor”—he raised his glass and smiled at her and she nodded—“or her hands I should say, drove the U’Donnor herd up by the Gate and…”

It took all Allistor had to not turn to look at his sister. Allisaid, sensing his tension, patten his knee under the table.

“Whose the hand?” she asked.

“Yer cousin,” Petten said. “Odhrán. He keeps a cabin close to where they too-” he paused and hid his face in a mug, then went on lowly, “but an hour from the Gate.”

Allisaid gripped her brother’s leg and he nodded. Odhrán was their aunt’s son, a twin to their father herself, but was a lone-child. Thus, he spent a lot of time with their grandmother and she was a… passionate woman, when it came to the Gate. She’d raised twins alone, her husband taken but so soon after their wedding. It broke her mind and she lived to the end of her days in the obsession of her fear and hatred for them. Were it not for her, they might had not left to join the Ash and all in the family had to swear an oath. Beware, beware…

While Petten kept going, starting with the gruesome sight he’d met only that morning, The twins looked at each. Odhrán always feared they’d come for him one day as well, for he shared their grandfather’s look, or so their grandmother always said.

Allistor motioned with his eyes to the exit. Outside the mist was thickening and Allisaid looked doubtful…

Choice

- …but she got up. They needed to check on their cousin. If nothing else, he’d be afraid.

- …and motioned to the Mayor instead. They needed to find out more and wait for the mist to part.

The trek was a relatively short one—or at least it should have been. The mist, thick as cream it was, made it hard to trust one’s footing. The twins knew the path well but also knew that lack of caution was dangerous; after the rain, the loose mud sucked on the soles of their boots, ever threatening to trip both siblings.

“I’m gonna say it,” said Allistor, “I haven’t missed this part onebit—it rains too damn much around these parts.” The man cursed all too loudly, breaking the silence of the dew-strewn field as the tip of his foot collided with a jutting stone.

“I quite miss it myself,” responded Allisaid with a sly smile, “the sound of it relaxes me, and the air feels that much smoother after all has been said and done. And the smell of wet grass is-“

“Only surpassed by the smell of dung, which is everywhere, all the time.” Allistor paused to look at his sister with furrowed brows, who in turn kept smiling until he returned the smile. “You’re allowed to have your opinion, sister dearest—even if it’s the wrong one.” He said in the end, teasingly and their journey continued once more. It was only after a few minutes—or was it more?—that Allistor broke it and spoke.

“I worry, you know. Our cousin was never known for his… steadiness—” spoke Allistor finally, though he was quickly interrupted by his sister.

“Let’s not jump to assumptions just yet,” she stated with a dip of her chin. “He found work, didn’t he? We’ll talk to Odhrán first and see what’s what. See? We’re close,” Allisaid nodded ahead, as the shadowed outline of a great, gnarled oak loomed in the mist ahead. “Odhrán’s cabin is north from here; that I remember.”

Standing directly in front of the tree, Allistor looked up. “We check the treehouse?” His sister nodded in agreement.

“He always did like to hide in that rickety thing when things got dire…” Quickly they went up the ladder and pushed open the hatch with a bang. There was no one inside; the place was silent as a grave, the gloom of the mist forcing him to squint to look around. Alas, some things are not hard to see.. Resting on a corner, a yellowed cow’s skull could be seen, interlaced with long strands of twine that each carried an item of their own as they hung closer to the ground: a smoothened pebble, a straw effigy, a bundle of horsehair, a lone feather, and other such things–too close for comfort to the trinket they had found in the field. With an almost instinctual nod of understanding, they looked around some more. Cocking his eyebrow, Allistor reached for a left-behind pair of boots. “Take a look at these—our cousin’s, I bet.”

Allisaid picked one up and examined it: besides and under the layers of mud and grime, there were splashes of crimson —blood. “Why?” she asked. “Why would he do this? If the others find out they’ll lynch him.” Then she went on, without waiting for an answer. “Come. We must make way for the cabin.”

Over and down a shallow hill, the cabin finally came into view, or at least the vague outline of its jutting chimney in the not-so-far distance. The mist seemed denser here—thick enough to cut with a knife, or so it felt like.

Before Allistor could take another hurried step, Allisaid grabbed her brother by the shoulder. “Stop,” she said. “Listen…”

A breeze blew past them; then came the rustling of leaves, many of them. No trees were in sight, however, nor were there any close by.

Allistor closed his eyes and let the sound wash over him. “It feels rhythmic—” he paused suddenly, turning to look at his sister. “I feel dizzy…”

Allisaid nodded and reached for her satchel. With a small pouch in hand, she turned to her brother. “I do too—here, smell this.” Her voice was forcibly calm but she could not hide her surprise and fear from her twin.

“Bah,” snarled Allistor, pulling back and rubbing his nose. “What in the fall is that?”

“Smelling salts,” responded the woman, cringing as she moved her nose over the pouch as well. “Maybe it will help. I think… I think they’re here.”

Allistor’s features tensed. “What now, then? We need to go get him—”

“This is too dangerous,” interjected Allisaid. “We need to think this through…”

Silent, the rustling of nonexistent leaves mocking them, the twins thought. A decision had to be made, and they could not afford to stall any longer.

Choice

- “We must go get our cousin, sister. You know this to be right,” said Allistor with determination and headed toward the cabin—Allisaid following him with a sigh, hand on hilt.

- “Remember our training. Slowly does it. We use the mist to our advantage, we surprise them if we can” spoke Allisaid, and her brother nodded begrudgingly—there was wisdom in that he could not deny.

- Neither spoke. He had provoked them. He had impersonated them. He had endangered the balance. The Fae must have their due.

The mist harbored within its dense shroud many an ill scenario, and the twins knew that well enough. Things did not make sense, nature did not act as it should, and there were powers beyond the mundane and the normal at play here. Of this, Allistor and Allisaid were now certain—though there were many questions to be answered still.

Brother and sister crouched low as they moved ahead, inching toward the now silent cabin with caution and stealth afforded only to the exceptionally trained—membership to the Ash Legion demanded as much. Allistor had his dagger drawn—short yet broad, with serrated teeth on one edge—and Allisaid had her hunting bow readied, a single arrow resting uneasily between her knuckles.

The rustling of leaves… of trees not to be seen still—yet whose presence lingered ominously—had now stopped. All sound, for that matter, had now ceased, and silence was the new constant that lorded over the misty backdrop. Soundless, it was deafening.

The twins dared not speak to each other directly, and, as they split—encircling the cabin like bestial predators sizing up their prey—it was the mock vestments of natural life that broke the silence.

An owl hooting; this Allistor called out with cupped hands. “Rear clear—no targets,” is what his sister understood.

The caw of an agitated crow came next. Its hoarse call all too familiar to Allistor’s ears. “Front—clear. No sign of hostiles,” confirmed Allisaid, prompting her brother to get up and join her before the cabin’s entrance.

The door was ajar, and no light came from inside. Allisaid peered from the crack, as her brother did the same from a window.

The interior was empty, dark, and hard to see within—though, at the very least, the mist had not infected it with its miasma. Without spoken word, brother and sister took positions at each side of the door, their weapons at the ready, but before Allisaid made her move, Allistor stopped her with a motion. Following his hands, she saw him reaching for a glass globe tucked neatly in one of his hidden pouches, and then shaking it with intent.

“Soffie, she’s a chapter mage,” mouthed Allistor with a self-indulgent grin, addressing his sister’s cocked eyebrow, before he rolled it from the opening of the door. An orange glow came from within it, growing as the ball rolled, and the light, unimpressive as it was at first, illuminated the gloomy insides of the cabin, as the twins burst in in unison.

No one. Nothing. Except…

Allistor exhaled as if making a point—his breath foggy.

Cold. Too cold.

“Winter’s a couple of months out still. Not inside our cousin’s shack, it seems,” he added, trying to hide his nerves behind his attitude but she motioned for him to quiet, her steps still careful, her eyes wide and alert. There was no source of cold, in the room. For this effect to be felt so strong, the magic funneled would have had to be impressive, recent or, more likely, both. Weapons still at the ready, they kept moving as silent as the creaky floor allowed them, sweat forming from the focus, despite the cold. Then, suddenly he spoke.

“Look at this,” Allistor all but whispered and Allisaid came to him. One of the side windows, the one facing west, was sealed shut—hoarfrost clung to it, the glass no longer clear.

Allistor pushed the window open, and the twins peeked over the edge. There were prints outside, of a beast not immediately recognizable, and they too were imbued with delicate slivers of ice.

“The forest… The Gate,” said Allisaid, and her brother agreed, prompting the two to move with haste and exit the cabin. The prints, vague as they were, led to more of their kind, and the twins found themselves marching through the mist once more. Not many paces after, the outline of trees—many of them—began to emerge in the not-so-far distance, and the siblings dreaded the sight of them.

“Damn them. Damn the Fae to hell!” grunted Allistor while panting. “What have they done to him?!”

“Calm yourself,” responded Allisaid curtly, never raising her gaze from the ground and the tracks. “You’ll tire yourself out.”

Not much time had passed, and the edge of the forest was now before both brother and sister. Dense it was: thick with bark and foliage to the point where it seemed impassable. “No more tracks,” stated Allisaid with a sigh. “We’ll have to—”

“There!” came Allistor’s voice, and the duo rushed forward. The figure of a man was visible. Sat down, head slumped, and his back resting against the knotted base of a large tree. They made to rush to his side but they stopped, shoulders falling defeated.

Quiet and angry, Allistor kneeled by his cousin’s side, his voice outlined by a plea. “Odhrán?!” he asked but expected no answer.

The corpse’s skin was ivory with streaks of blue where there had once been veins—the flesh hard and frigid. Odhrán’s nose was blackened, and so were his lips; worst of all, however, was the flower. It had bloomed from the mouth—or so it seemed—its stem reaching deep into the man’s gullet. It had thorns along its length, and its petals were mixed, some wide and of the darkest midnight blue, others like blades of white snow.

“Like an edelweiss kissing a rose… I’ve never seen the like of it,” muttered Allisaid between sharp exhalations, but her brother was not as calm.

Allistor pushed the head aside reflexively, but the body moved little. Rootlings—minuscule and thin, but there were hundreds of them—jutted out of the soil, clinging onto Odhrán’s deceased figure like hair embedded in skin. Both twins stood up and took a few steps back, as the forest itself sighed amidst the rustle of leaves and the creaking of branches.

Beware! Beware! And lie not, ne’er, through word or foul deed.

Now this forked tongue, this liar young, for once shall bloom true seed.

“The tree…” Allisaid muttered, wide-eyed awe mixed with wonder. “The tree sang to us. I’ve never…”

“He’s dead!” spat Allistor, his voice trembling. “They killed him… Like all the others.”

“No,” came Allisaid’s response, the woman pushing aside the forest’s windswept message from her thoughts. “This is different. A body behind… Why?”

“Who cares?” he answered. “They crossed the Gate. They killed in our land. The others must know. We must warn the others! We must warn everyone.”

“No!” she rushed to silence him. “You saw what he had done. He’d staged these attacks… He tried to provoke them. He tried to provoke us. I think they’re trying to pass on a message. A warning. Didn’t you hear? Lie not, ne’er, through word or foul deed…”

“Noone will see it so,” Allistor said. “I don’t see it so. What next, eh?” Allistor felt his chest tighten and turned to face his sister. He was scared, she saw, just as she was. Scared and angry. “If he had committed crimes, they were our crimes to punish. They didn’t have the right. This is an attack. They didn’t have the right.”

She shook her head, uncertain.

Choice

- “We tell the others the truth,” spoke the sister, and her brother nodded in agreement.

- “We bury the body and speak not to a soul of this,” concluded the sister bitterly.

Interlude

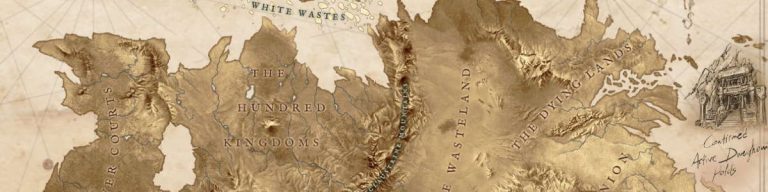

In 303 P.R. Perin I, son of Charles Armatellum and First Emperor of the Telian Empire, passed away. His son Charles assumed the throne under the moniker ‘the Second’, despite his legendary grandfather never having been an Emperor. History, however, would remember him as Charles the Conqueror. True to the heritage of his name, Charles II would bring to heel through war or diplomacy all that was left of the Flaegrian basin, carving with steel the borders that would shape the Empire since. In the east, he won the hearts and minds of the Russ, his son sealing with marriage an alliance that would last centuries. In the North, he reclaimed all those lands that Svarthgalm and the Nords had conquered. In the south, he pushed all City States forces beyond the mountains, sealing them in the hard-rock peninsula beyond, while he conquered Aellum, the “Indomitable City” of the Plains, even if it was for but a scant few years. But his greatest challenge, it is said, came in the twilight of his reign. His greatest challenge was in the northwestern lands.

The history of what followed is mundane: Charles the Conqueror wanted the lands of the old Keltonni to join the Empire proper and, to do that, he needed a way to win their hearts and minds. But the mundane turned to legend, and legend into myriads of myths; some with ancient Keltonni legends reborn. Others with druidic champions forging fabled weapons. Others still, with epic duels between the King of Cold Iron and the Prince of Rime, or even with strange women lying in ponds distributing swords. All of them filled with the Fae Beyond the Gates, the Weavers of the Forests, the Children of the Faerann. And none of them remembering that it started with a letter. A letter from a twin pair of siblings, legionnaires of Ash that had far exceeded their authority in chase of a family feud.

It said that the Weavers had attacked and it was all the Emperor needed.

The Highland Sea.

658 P.R.

“Some day, this is…” Niall muttered.

The heavens roared with distant thunder, and the waves buffeted the hull of Ol’ Isla with creeping intensity. Niall took in a deep breath, the air crisp and cold, and sat down with shaky legs, holding onto the tiller as he tried to steer the boat as best he could. Every so often, the man would reach for a wooden bucket at his feet, scooping up water and flinging it overboard with trembling hands. At one point, as he swept away the sea and salt from his eyes, he almost smiled, remembering Ewan. “Ye stayin’ out?!” the man had cried from his own boat. “I’ll be back before sundown!” he had answered. “Don’t ye worry!”

He muttered the last sentence again now, eyeing the dark horizon. The land of his home was lost now, well and truly out of sight, and in its stead, something new had emerged to replace it, as the current and the wind carried him ever west.

Great cliffs joined to form a jagged coast, scattered rocks like sharp teeth flashing white as wave upon wave crashed against them. Niall felt a heaviness deep within his chest—a lead weight had settled within the pit of his stomach and would not budge; he couldn’t let himself be carried further, he knew. Scanning for passage among the rocks and for less than a certain death of a landing, he finally saw as close to the beach as he would. The man pulled the hood of his cloak closer and reached for his chest, feeling a familiar bulge underneath his tunic, exhaling with relief as he thumbed it. Then he pulled together all his skill and experience and tried to head to shore. He almost made it.

“Shit,” that’s what he tried to say—to scream—but the water rushed into his mouth and made him gurgle instead. Ol’ Isla had been capsized, in an instant, shoved against an unseen rock by a rampaging bull of a wave. The crash still echoing in his mind, Niall lashed out, and both arms grabbed onto the overturned hull, feeling his nails dig into the wood’s fibers as he fought against the pulling of the water.

He had almost reached the shore, and a narrow beachfront could be seen among the daunting mesh of cliffs and jutting rocks. Ol’ Isla creaked and groaned amid her death throes, and Niall felt the boat—what had remained of it—buckle under the pressure of the buffeting waves.

With a prayer on his breath, the man let go and swam; he swam like never before, beating upon the water with flailing arms as he tried his best to keep the sea out of his lungs. Like hours they had seemed, those brief moments, while he spent all that he could to reach the shore. When he finally did, there was no triumph to it; Niall simply washed ashore like a waterlogged carcass, retching violently as he gasped for air devoid of salt and water.

He dared not walk—he could only crawl—and the pebble-strewn surface of the beach pulled apart his clothes. Uncertain if the wetness he felt was rain or the sea reaching him still, he crawled weakly before he finally stopped. The wind howled, and the sea roared, but even amid such chaos, Niall thought he heard…

He shivered, though cold was not the culprit, and he felt the hair at the back of his neck rise. Only now it really landed, where he was stranded. Only now did fear truly grasp his heart and innards with long, cold fingers. Struggling to keep his eyes open, he turned on his back, the sweet water little and cold comfort, as the rain whipped his face. With trembling hands—from fear, cold, or exhaustion, one could not tell—he reached inside his torn shirt and pulled something out. He saw flashes of his daughter, with hair the color of straw, leaning over her pile of twigs and petals and feathers, as she busied herself with the curios and trinkets she had loved so. Every time before he went fishing, on every holiday, and every full moon too, she’d bring them offerings—and in the midst of them, always, the charm he had taught her. The charm he also held in hand. Niall felt a shiver run down his spine anew and reached for his chest, pulling out the same charm now. And as his eyes finally closed weakly, he prayed her offerings would prove enough.

Choice

- It is Winter he has landed upon.

- It is Autumn he has landed upon.